Research

Mining the cultured and uncultured biosphere for new drugs

Evolved small molecules have proved a prolific source of therapeutics, accounting for a significant fraction of currently marketed drugs. However, discovery efforts to date have focussed on a narrow section of the tree of life. For instance, Actinomycete bacteria from soil have been extensively mined, and there is now a very high compound rediscover rate using traditional methods of culture and isolation. Through culture-independent (metagenomic) sequencing and bacterial genomics, we know that there are a plethora of unexploited bacteria that are capable of making small molecules. However, there are two main problems in mining this unexplored majority. The first is that most species of bacteria have never been cultured and may not be able to grow alone. For instance, there are many cases of eukaryotic organisms forming symbiotic relationships with bacteria that produce protective compounds. Over millions of years, symbionts can become dependent on their host, and cannot be grown independently. The existence of such long-lived symbioses suggests that their protective compounds are highly optimized and of potential therapeutic interest, but also that the producing organism is less likely to be culturable. The second problem is even when bacterial strains are culturable, they often do not express all their biosynthetic potential in the laboratory, meaning that cultured bacteria typically only yield a subset of small molecules they are capable of making. We are currently employing a number of parallel strategies to solving these problems. These include genome mining, synthetic biology and bioinformatics.

Funding: NIH NIGMS R35

Development of metagenomic binning algorithms

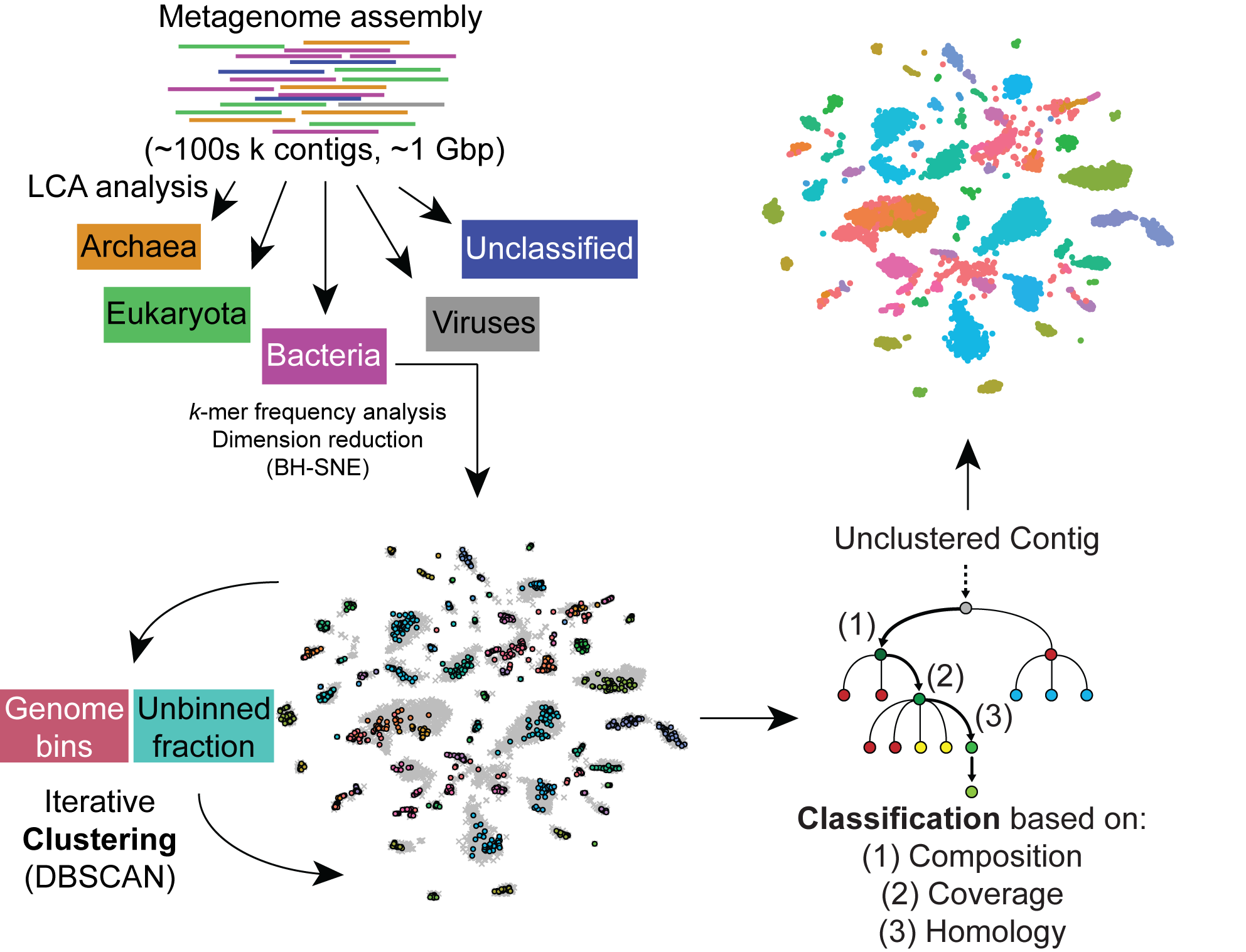

In the environment, bacteria and other microorganisms hardly ever exist as monocultures, but instead live in communities of varying complexity, often associated with or inside a more complex organism, such as a human or marine invertebrate. It is thought that small molecules are important to the function and balance of such communities, but functions of individual molecules are often shrouded in mystery. Because most environmental bacteria have never been cultured, studying microbial communities often requires culture-independent sequencing to characterize the genomes of each species present. The problem with reconstructing genomes from metagenomes is that assembled sequence data typically consists of millions of sequences, each representing a section of a genome amongst an unknown number of species. Additionally, environmental sequencing can often contain uncultured species that are previously unknown to science, so reference genomes cannot be used. We have been working on algorithms to automatically separate genomes from metagenomes (called "binning"), even for highly complex communities associated with hosts that themselves have unsequenced genomes. We have released the first version of our pipeline, called "Autometa" (see Software), and we are also working on a number of planned improvements. In particular, we plan on improving Autometa's performance so that it can handle soil metagenomes, which are some of the most complex microbiomes on Earth. This work will support our other metagenome mining efforts, and allow us to unearth fundamental insights into how microbial communities work.

Funding: NSF CAREER

Autometa workflow